In the past week I’ve faced two of my hardest physical challenges ever: the Brazen Dirty Dozen endurance race July 12, followed nine days later by a single day climb up and down Mt. Whitney, the highest summit in the continental United States. Why attempt two such difficult endurance tests on back-to-back weekends? It was sheer stupidity on my part, but I survived, and may even be stronger as a result.

The Brazen Dirty Dozen

First up was Brazen Racing’s “Dirty Dozen” and half dozen trail races: run as far as you can in 6 hours (half dozen) or 12 hours (dirty dozen). Unlike typical races, in this format everyone runs for the same amount of time, and the winner is the person who covers the most distance. What kind of sick person would even attempt a race like that? Apparently, someone like me. Having never before run further than 26 miles in 4 hours, I decided the 12 hour, full dozen event would be suicide, and opted for the half dozen 6 hour race instead.

The Dirty Dozen race was on mostly level trails at the Pinole Seashore, on the San Francisco Bay north of Oakland. The main course was a 3.3 mile loop with about 100 ft of elevation gain and loss. During the last hour of the event, Brazen also opened a second 0.6 mile loop. Only complete loops counted towards your distance total, with no partial credit, so the goal was to arrange yourself to finish your last loop just before the clock reached 6:00:00.

Prior to the race I’d been having a lot of trouble with both ankles and one knee, due to several unrelated running and hiking accidents over the previous weeks. Until a few days before the race, I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to do it at all, but the injuries seemed to heal just in the nick of time.

We started off at 7:00 am on a cool, cloudy morning with a light breeze. Unsure how to pace myself or what distance I should expect to run, I decided simply to take it very easy, and make my goal be to keep moving for six hours, whatever the pace. If I felt like I needed to slow down or walk, fine, as long as I kept moving. I settled into a pace around 9:00 to 9:30 per mile, which was a very easy effort level for me, equivalent to an easy jog or recovery run. I chatted a bit with the other runners, learning who was an ultra running veteran, and who was a first timer like me. I was a bit in awe of the people running in the 12 hour category, and took their advice to keep the pace slow and relaxed.

The laps went on and on. It remained cool and cloudy for the first four hours, though it did get warmer towards the end of the race. I never really had a problem with the knee or ankle. There were some random knee pains briefly about half-way through, but they went away and never came back. So I just kept running. With the loop format, after a while everyone was on a different lap, and I didn’t know where I stood in the overall field. When I passed someone, I didn’t know if I was moving ahead of them, or lapping them, or if they were already a lap up on me. But it didn’t seem like many people were running as fast as I was, and I was rarely passed, so I guessed I was doing pretty well.

Unlike virtually every other race I’ve ever done, I ate and drank a ton! Normally for a marathon I would eat some Gu or Shot Bloks, and that’s about it. But in this race I ate boiled potatoes, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, potato chips, pretzels, soup… everything. I might have taken in 1000 calories or more. It just seemed like the thing to do, and the aid stations were well-stocked with a smorgasbord of food.

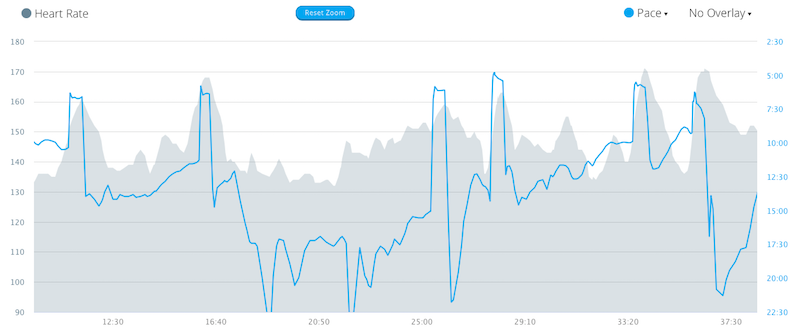

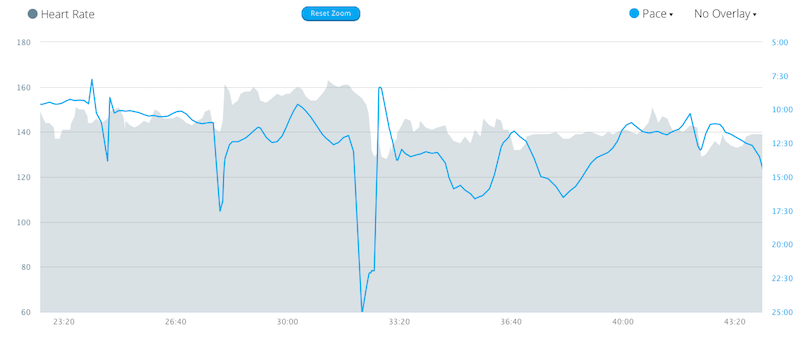

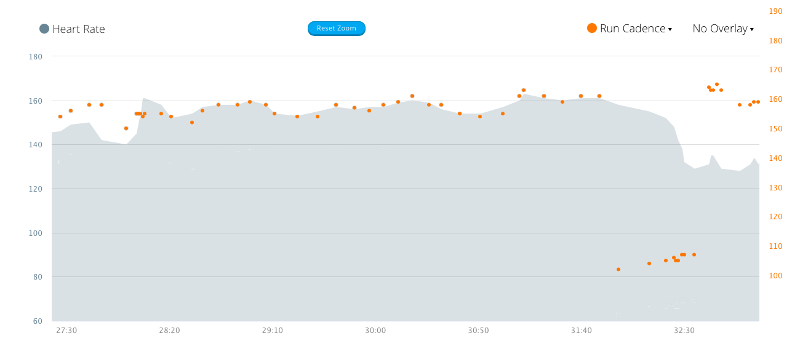

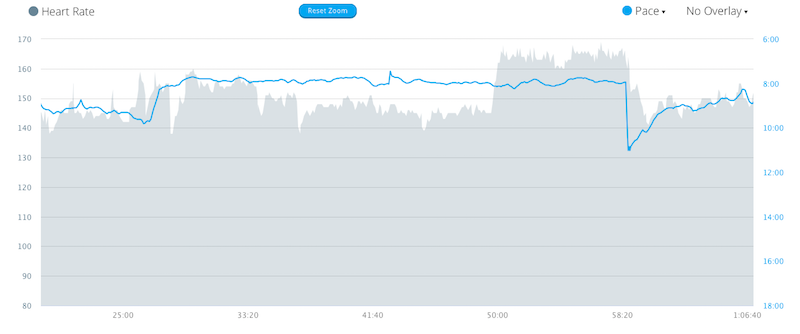

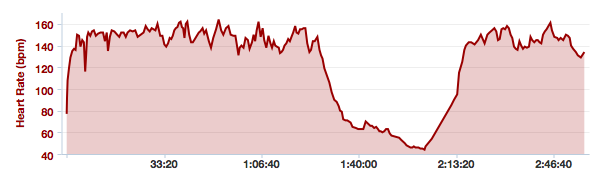

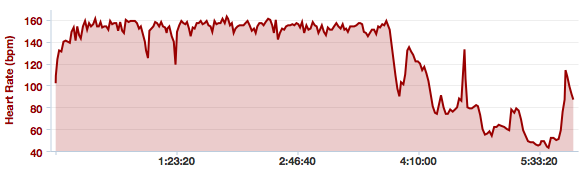

I kept running, and running, and running. Except for a few seconds to grab some snacks at each aid station, I ran the entire way from start to finish. I kept up a pretty steady 9:10/mile pace for the first four hours, then I faded a little to a 10:00 or 11:00/mile pace for the last two hours. I was getting exhausted. Mentally I think I was prepared to run a marathon distance, but no more. So when I crossed the 26.2 mile point and realized I still had lots more running to do, it was like getting a kick in the face. During the last big loop, I was kind of a wreck, talking to myself out loud, and just trying hold everything together for a few minutes more. As the clock ticked down, I had time to squeeze in one lap of the 0.6 mile loop too, finishing up in 5:56:52, staggering over the finish line in tears.

I had run 37.33 miles. Jesus God, that is far – almost 50% farther than I’d ever run before. Crazy far, like the distance between two cities. I avoided injuries, and I didn’t have any joint pain or blisters, but physically I was a wreck. I wobbled drunkenly around the finish area, wanting desperately to lie down, but afraid that my muscles would spasm and lock up if I stopped moving. So I stayed on my feet, and stuffed my face with ice cream, bagels, and Gatorade.

The results were posted about half an hour after the finish. I thought I’d done OK. On a good day, I can usually finish in the top 10% or 20% of the overall field at most races. I checked the results, and the winner had gone 41 miles. My 37.33 miles was good for 3rd place overall out of 182 people, and I won the M40-44 age group! Holy cow!

I missed a couple of splits near the end of the race, but it went down roughly like this:

Long Loops (3.33 miles)

1: 30:37

2: 29:45

3: 30:42

4: 30:32

5: 30:10

6: 30:53

7: 30:51

8: 31:39

9: 34:13

10: ~35:23

11: ~35:22

Short Loops (0.65 miles)

1: ~5:54

My marathon time was 4:02, and my 50K time was 4:51.

Overall, the Dirty (Half) Dozen was an interesting and exciting event. But I think I’ve been cured of any desire to do another ultra. Maybe, maybe I could do a 50K, but that’s about it. After finishing 26.2 miles at the Dirty Dozen, I just really didn’t want to be there anymore. TOO LONG!

Mt. Whitney in a Day

Nine days later, I found myself at Whitney Portal in the Sierra Nevada mountains, about to begin a single day hike up and down Mt. Whitney. At 14,508 feet, Whitney is the tallest mountain in the continental United States. The trail from Whitney Portal is 22 miles round trip over rocky terrain, with 6200 ft of elevation gain, and the whole distance at high altitude where oxygen is scarce. Smart people make the trip over several days, camping along the way. Only idiots like me attempt to do the whole thing as one giant day hike.

I’d been wanting to climb Whitney for a few years, but it wasn’t until this May that I happened to check the park service web site, and found there were still day use permits available for July. I grabbed two permits for July 21, convinced my friend Jeff to join me, and started making plans.

I’m in pretty darn good physical shape. I run 40+ hilly miles per week, and I do marathons and ultras. I’ve climbed three previous California “fourteeners”, and a couple years ago I hiked most of the John Muir Trail from Yosemite to King’s Canyon. So I assumed the warnings I’d read about how demanding the Whitney day hike is didn’t apply to me, and we’d be up and down the mountain far faster than average. Ha! The mountain kicked my ass.

Our acclimatization began on Saturday with a drive up to Yosemite and an easy hike around Tuolumne Meadows (8600), then spending the night at Mammoth Lakes (7800). Sunday we picked up our permits in Lone Pine, then did a day hike from Horseshoe Meadows up to Trail Pass and Mulkey Pass (10500). We spent Sunday night at Whitney Portal (8300) before beginning our hike early on Monday morning.

We awoke at 2:00 am, wondered what the hell we were getting into, then were on the trail at 2:35. We checked the scale at the trailhead, and my pack weighed 15 pounds including 2L of water. I carried:

- ULA Catalyst pack

- 2L water

- katadyn water filter

- two headlamps

- 2500 calories of trail mix, energy bars, fruit, etc.

- lots of extra warm clothes, most of which I ended up wearing later

- first aid kit

- emergency bivy sack

- compass

- sunscreen

- camera

- maps and timetable

- WAG bag

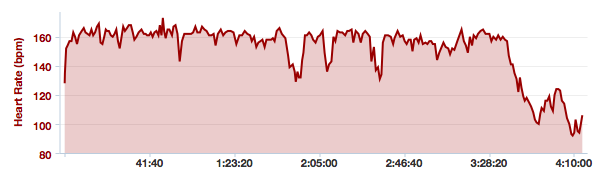

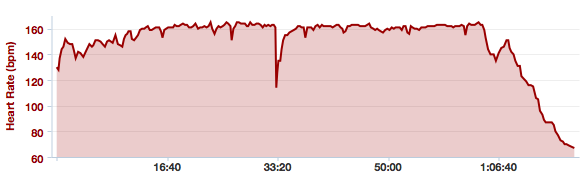

We started off well, and I really enjoyed hiking in the dark. Our headlamps gave plenty of light to see what we were walking on, but not enough to see much around us, so it was like hiking through a dark tunnel. Occasionally we stopped and turned off the headlamps to gaze at the stars, which were tremendous. Around 4:45 am, somewhere past Mirror Lake, the sky began to glow a dull orange. Watching the sunrise and the alpenglow was incredible. I loved every minute!

Around 3 hours into the hike, Jeff began to lag. Up to that point we’d been averaging about 2 miles per hour, joking and singing as we went, but he quickly grew quiet and said he was feeling tired. We continued on, but more slowly than before. Our strategy the whole way up was to hike at a slow and easy pace, but keep going without any breaks except the occasional stop to remove a layer of clothing or get something out of the backpack. In retrospect, maybe we would have done better to take a 10 minute break every hour or so. After six hours of hiking we finally reached Trail Crest, the point at 13,800 ft where the trail crosses the ridge line onto the back side of the mountain. Jeff was not having a very good time. He was determined to keep going though, and said he would “dig deep” to make it to the summit.

My secondary goal was to climb Mt. Muir, a 14,019 foot peak only a short distance off the Mt. Whitney trail. From what I’d read, it was a fairly easy detour from the main trail, and only a few hundred feet up to Muir’s summit, involving a small amount of class 3 scrambling at the final summit block. It wasn’t clear to me exactly where Mt. Muir was or where to detour from the main trail, though. All the rocky outcroppings looked the same. Eventually I located it, and after some discussion, we decided Jeff would continue slowly on towards Whitney summit while I climbed up Muir, then returned to the trail and caught up to him from behind. I followed a faint use trail up the pile of rocks towards Muir’s summit block. It wasn’t great. There was nothing super difficult about it, but I was moving very slowly, climbing with hands and feet, and searching out the best direction to continue up after every few steps. After ten minutes I made it about half way up to the base of the summit block, then stopped and stared up. I looked long and hard at the summit block, and decided no, not today. If I’d been with someone more experienced who could have helped guide me up, I think I would have been fine, but I didn’t feel like pushing my luck while hiking there alone. So I chickened out and climbed back down to the trail, which was a lot tougher than climbing up had been.

This is as close as I got to the top of Muir. Somehow it looks a lot closer in the photo than it did in person.

I hurried to catch up with Jeff, reaching him about 15 minutes later. He was still moving forward slowly, with a look of grim determination on his face. This section along the ridge was absolutely incredible, with strange rock fins and pinnacles poking up everywhere, and dramatic drop-offs to the right through the “windows” between sharp needles of rock. I felt like we were really mountaineering now. We kept going, reaching a point about half a mile from the summit before Jeff stopped and said “I’m not going to make it”. I was about to reply with some motivational gambit, when he turned and vomited on the trail, retching over and over until there was nothing left in his stomach. Then he sat, feeling slightly better after the vomit. Groups of people appeared suddenly coming from both directions, seemingly unconcerned about stepping in the pile of vomit in the middle of the trail.

Years ago while climbing Mt. Shasta with Jeff, I got sick around 12500 ft, and he abandoned his summit attempt to hike back down with me. I was prepared to do the same for him there, but after 10 minutes of rest he felt well enough that he wanted to continue. We knew we had less than 30 minutes of hiking left to reach the summit, so off we went. Before long the roof of the Smithsonian hut crept into view, and then we were there. Hallelujah! I ran around shouting and fist pumping while Jeff collapsed on a rock, exhausted. Our total time from trailhead to the summit was 8:15.

The weather was great at the summit, with about two dozen people milling around in the sun. A layer of puffy clouds hung below the summit. Then I did something I’ve never dared to before: crept up to the very edge of the east face, sat on the last rock, and dangled my legs over the 3000 ft drop straight down. I was terrified and my heart was racing, but it made for a cool photo! 🙂

After about 25 minutes, we started back down. Jeff ate a little, and began feeling slightly better. As we descended, our conditions seemed to reverse. He began to perk up, while I started feeling crappy. By the time we got back to Trail Crest, he was in good shape, but my head was pounding and I was exhausted.

The rest of the miles seemed to last forever. The whole way down stretched out interminably, and I kept thinking we were farther along than we really were. I lost track of the number of times I said “I don’t even remember hiking up this.” Any sense of enjoyment in the hike was completely gone, and I was fully in zombie survival mode with no thought other than to reach the bottom. I think the altitude was certainly a factor, but the main problem was just exhaustion. The trail just went on and on, forever. It took us 6:55 to make it down, which wasn’t much faster than our time on the way up. Including time spent at the summit, the whole hike took 15:10 round trip. When we reached Whitney Portal at 6:15 pm, I was completely wrecked. I was almost in tears. But after some food and an hour’s rest, I bounced back and was feeling half-way normal again. Wow.

It was an awesome hike, and I especially enjoyed traveling in the dark, watching the sunrise from the trail, and traversing the ridge near the summit. But I think you have to be an idiot to want to do this as a day hike from Whitney Portal. Either that, or you need to be in outstanding physical shape and practically immune to the effects of altitude. With my prior conditioning and endurance running, and two days spent acclimatizing, I thought I could handle the Whitney day hike without too much trouble. I was wrong, and the last few hours of descent were completely miserable. If I ever climb Whitney again, it’ll definitely be as a two or even three day camping trip, and none of this day hike craziness. My hat’s off to those who can do Whitney in a day and return in one piece. That is one hell of a tough hike!

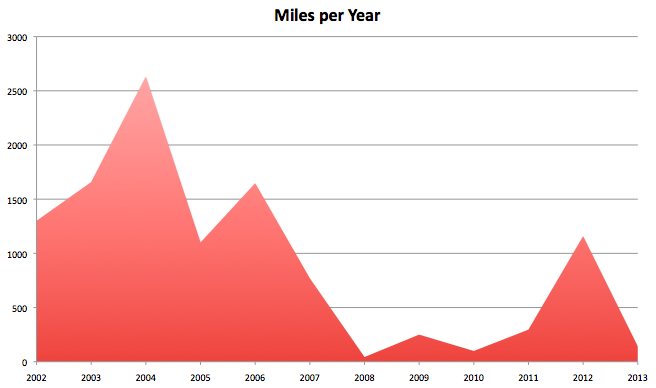

Anyone ages 9 to 90 can get outside and run, but if you’re competitive and enjoy racing, it sure helps to be young. As you age past 40, and the days of setting new personal bests are behind you, what motivates you to keep going? Do your reasons for running change as you get older? And what can an older runner do to stay competitive?

Anyone ages 9 to 90 can get outside and run, but if you’re competitive and enjoy racing, it sure helps to be young. As you age past 40, and the days of setting new personal bests are behind you, what motivates you to keep going? Do your reasons for running change as you get older? And what can an older runner do to stay competitive?